What caused Katrina?

A simple question, until we dig a bit deeper into the terms. By Katrina, do we mean the failure of the levees? Do we mean the meteorological storm? Or, are we speaking of the breakdown of society occasioned by a combination of levee breaches, power failures, and government ineptitude? Are we asking a question concerned with meteorology, engineering, or social psychology? Additionally, when we speak of cause, how do we define the term? Could there have been one “cause” for an event so devastating as Katrina? Do catastrophes ever have a single cause?

One possible way to understand Hurricane Katrina and what happened in August of 2005 is suggested in Ubiquity–Why Catastrophes Happen by Mark Buchanan. Mr. Buchanan is an author, physicist, and blog writer who examines the relationship between physics, events, and history. Published in 2000, Ubiquity explores how an experiment by three Stanford physicists led to a field of study that can help us understand how catastrophes occur.

In 1987, Per Bak, a theoretical physicist and two of his colleagues at Brookhaven National Laboratory conducted a series of “games” which were presented in a paper published by the Physical Review of Letters. The games consisted of dropping grains of sand on a table and examining how the piles grew as more grains were dropped. The piles were, of course, simulations based on a computer program designed to mimic “real world” sandpiles. In the simulations, the piles would grow and reach the point where one more grain of sand would cause an avalanche. Bak was interested in how and when these avalanches would occur and the magnitude of the failures.

As Buchanan described the game:

To understand this “sandpile game,”… imagine dropping grains of sand one by one onto a table and watching the pile grow. A grain falls accidentally here or there, and then in time the pile grows over it, freezing it in place. Afterward, the pile feels forever more the influence of that grain being just where it is and not elsewhere. In this case, clearly history matters, since what happens now can never be washed away, but affects the entire course of the future. [Emphasis added.]

Bak and his colleagues ran the simulations thousands of times and the results? In one sense, there was none. Bak found there was no such thing as a “typical” avalanche. Some piles resulted in small avalanches. In others, an incremental grain of sand would lead to a pile-wide collapse. How can this be? Bak theorized that as additional grains fell on certain piles, sometimes “critical states” were created. A critical state is defined as an unstable pile that might or might not collapse with the addition of one more grain. As Buchanan wrote:

After the pile evolves to its critical state, many grains rest on just the verge of tumbling, and these grains link up into “fingers of instability” of all possible lengths. While many are short, others slice through the pile from one end to the other. So the chain reaction triggered by a single grain might lead to an avalanche of any size whatsoever, depending on whether that grain fell on a short, intermediate, or long finger of instability.

Can “fingers of instability” and the “critical state” help us understand the events surrounding Katrina? In some sense, yes they can. If “fingers of instability” refer to the pre-conditions that might lead to an avalanche or catastrophe, certainly the city of New Orleans had, and has many such fingers. Some conditions include:

- Geography – the citing of the city in 1718 has presented unique challenges to the metropolis throughout its history, not the least of which is the topography or “bowls” that form the city. See van Heerden. From the first levees built at the direction of Bienville to the current Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS) managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans has always faced the threat of flooding. Additionally, while land along the Mississippi is above sea level, urban sprawl and development led to construction in areas that are not only below sea level, but effectively trap rain or flood water. Only the city’s extensive pumping system makes these areas habitable. Thus New Orleans is faced with the dual problem of keeping water out as well as expelling the rain and ground water that accumulates within its borders. For extensive discussions of these problem, see Campanella 2002, Horowitz.

- Navigation – decades of economic development with little regard to the long-term effects of such development led to the construction of the Industrial Canal and the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (MRGO). While the advancement of commerce and employment was an admirable goal, there was little or no consideration of the environmental impact of these waterways. This fact was driven home post Katrina when the Army Corps of Engineers permanently closed MRGO in 2009.

- Resource Extraction – the damage to the wetlands and ecosystem of the Gulf Coast caused by resource extraction is well documented. Historically, this barrier slowed storm surges and lessened the strength of approaching hurricanes, but extensive land loss in the last 40 years has removed this natural impediment. For detailed discussions of the history of this destruction see Colten (2021), Arnold.

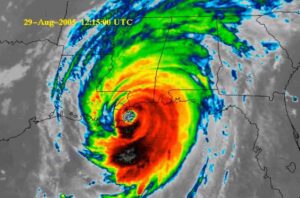

- Power Grid – when Katrina made landfall in Louisiana, power was lost in most of the city in the early hours of the 29th. The loss of electricity had a cascading effect on the operation of pumps, communications, and healthcare. Similarly in the much stronger Hurricane Ida, power was lost early in the storm and remained out for over two weeks in some areas. While the levees performed admirably during Ida, the failure of the Entergy power grid cost lives and caused massive suffering.

- Government Mismanagement – while the shortcomings of Brown, Bush, Nagin, and Blanco are well documented, one little discussed fact is that Louisiana had lost it head of emergency response efforts just eight months before Katrina struck. In November of 2004, Michael L. Brown (not related to Michael D. Brown of FEMA) was indicted for obstructing a government audit and later resigned from the Louisiana Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness (LOHSEP). He therefore was not involved in the response to Hurricane Katrina, and perhaps Brown’s presence during Katrina would have changed Governor Blanco’s efforts. (Brown was later given probation and a small fine as a result of the indictment.)