Mutinous Women by Joan DeJean

Law deported convicts to settle New Orleans and sent over prostitutes to marry them. (Emphasis added.)

Such was the long-held belief, even among historians, about the founding women of Louisiana and the Gulf Coast. That belief has been demolished in a new book by Joan DeJean, professor of romance languages at the University of Pennsylvania. Mutinous Women – How French Convicts Became Founding Mother of the Gulf Coast (Basic Books 2022) tells the story of the over 100 women who were forcibly removed from France and played major roles in the creation and development of the Gulf Coast. Using records from the French National Archives as well as other sources, DeJean tells the stories of these women in amazing detail. Family backgrounds, legal entanglements, deportation, and their subsequent lives in North America are recounted by the author combining the tools of a genealogist with those of an historian. Most importantly, DeJean delves into the backgrounds of these women to show how most, if not all the deportees were the victims of a French legal system that wrongly convicted these women.

After sham legal proceedings, these women were deported on two ships late in 1719 and early 1720 to what was then termed the “Mississippi” colony. At that time, the colony was at the center of John Law’s attempt to expand the French presence on the Gulf Coast. The Regent had appointed Law to create a commercial venture centered on the colony in order to reduce France’s enormous debt. Law’s scheme and the stock market bubble that resulted from Law’s efforts are well recounted by DeJean using a variety of sources including french texts that have yet to be translated into English. (See Giraud, Volumes III and IV.) It is the author’s ability incorporate these previously overlooked materials into her analysis that makes this book such an important contribution to the narrative of the colony’s founding.

DeJean’s work excels in several other ways. First, she tells with great detail how these women settled in various areas of the Gulf Coast and made lasting impacts on the growth of the region. The author recounts how these women settled and created Biloxi, Mobile, Natchez, the German Coast as well as New Orleans. DeJean follows these women from their landing on the shores of the coast, to their marriages, children, and commercial ventures. Second, DeJean describes the horrendous conditions that the early settlers (male and female) endured in the new colony. As DeJean writes, “The ones who returned to France may have been the lucky ones. Due to famine, disease, and the colony’s dire economic situation, perhaps as many as seven thousand of the roughly nine thousand individuals transported to Louisiana on Indies Company vessels during Law’s tenure died soon after arrival.” Third, DeJean gives an excellent account of the frenzy created by John Law’s system. DeJean notes the central importance of tobacco as the hook that drew such massive interest in the colony. DeJean then shows how the Mississippi Bubble and Law’s outlandish promises created the incentives for the deportation of these women.

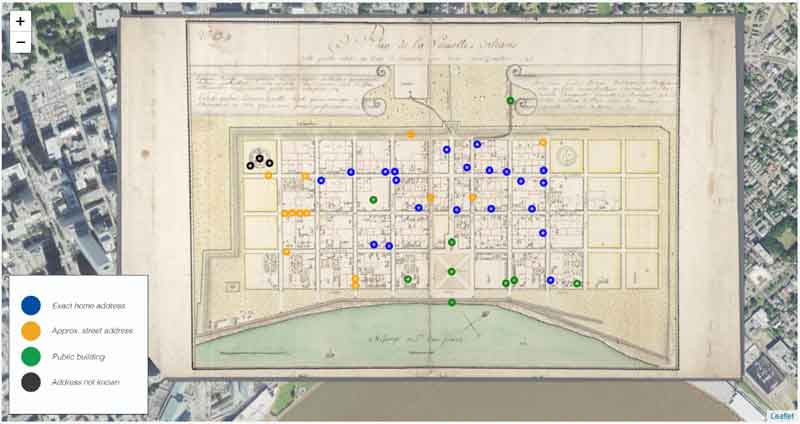

As an adjunct to the book, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have created a companion interactive map showing where some of these women lived in 1731 New Orleans. For example, Marie Louise Brunet who arrived on the vessel Deux Frères lived at the intersection of Royal and Orleans, just behind what is now St. Louis Cathedral. The web map was created by the author with digital assistance from Cassandra Hradil and Pauline Carbonnel. The map can be found here. Below is an image of this map.

DeJean has written an important work that has added significantly to our understanding of what Iberville, Law, and Bienville established. Writing with compassion for these women, DeJean has demonstrated how this group of women should also be recognized among the “founders” of the Gulf Coast.